Heaven's Gate by Michael Keir-Morrissey

My Uncle Michael's enchanting account of family camping holidays in Fiordland from the late 50's to early 60s.

My Uncle Michael's enchanting account of family camping holidays in Fiordland from the late 50's to early 60s.

Every year the gates of heaven opened at 8.40am. This was new year 1959, but from the mid 50s right into the early 60s we followed the same exciting track. As always Mum had micro-managed everyone into the Blue Star taxi that brought us here. Dad paid the driver six and six. Walking into the station too excited to talk, a sight and sound feast kept our eyes swivelling and ears alive, clocking every flashing detail.

Christchurch Railway Station c1958, new station rising behind opened 1960

On the platform - familiar awe. The same players were lined up. Rows of windows - glinting pools in red - suitcased people climbing in a door, curving carriage roofs. Mum and Dad would find our seats and ‘if we were quick’ we could pay tribute to the power waiting up ahead. Panting, creaking, all hot and fiery the Ja, a perfect panther, stood hissing and impatient on its gigantic wheels, its headlight pointed south. We had plenty of stations ahead to visit, so this was just a bow to the beast to reconnect with last year. The crew looked ready. The driver leaned on the window ledge while the fireman shoveled more coal into the flames. Enveloped in billows of smoke and steam they always had a few last words for comrades on the platform, and sometimes a benign look towards us.

Ja 1254.

Almost 8.40 and the heavenly gates were about to open. Time to dash back to the last carriage to find Mum and Dad. We had to be aboard to hear the whistle blow so Mum was relieved now to be able to point out where we should sit. We took up three rows of double seats, each window seat the throne. Our eldest brother was lucky enough to claim a ‘single’ if he was with us. Above our places the reservation card showed we were going the whole way. ‘Christchurch to Invercargill’. We were travelling on Dad’s ‘priv’. In those more equitable days a railway worker could claim a yearly ‘privilege ticket’ that allowed the whole family free first class travel. Dad was a carriage-maker, he and his colleagues built the superstructure and varnished interiors of the carriages we rode in. These grand accommodations were the setting for our spectacular and exhilarating twelve hour procession via the country and the towns to the farm, and the wonders of Fiordland and Central Otago that awaited us. The guard’s strident whistle blew answered by a haunting blast from the steam engine and ever so slowly the train inched away from the station pandemonium. The annual southern pilgrimage had begun.

NZR First Class Carriage 1950s

The South Island Limited took almost two hours to reach Ashburton, the first ‘refreshment’ stop. It was exciting to manoeuvre amongst crowds surging at the trough, with its warm smell of pies and cakes, tea and coffee, and to make it to the glass-fronted counter where the bottles of raspberry fizz we called ‘red’ were available. Another two hours later we saw the blue sparkling sea at Timaru’s Caroline Bay and gladly said goodbye to the Canterbury plains. Lunch was served at Oamaru, the dining room guarded by an unsmiling maître d’ whose baleful stare we always found scary. Not that we used the facilities - one of Mum’s sandwiches sufficed as we watched the arrival of another huge Ja steam engine to couple with the first and together haul us through the hills and tunnels to Dunedin.

After all the backyard views of various towns so far, it seemed wonderfully strange leaving Oamaru through the middle of their Botanic Gardens on our way up to the first big tunnel and then on to Herbert. Thereafter, embraced by forest clad slopes and green farms we snaked through the gigantic sheep spotted hills. From our seat in the last ‘car’ we loved to catch a glimpse of the two massive Ja's working their heart out up ahead - all smoke and scalding hot steam as they chuffed and charged around one of the wide climbing bends leading the curving red line of carriages. We blew in and out of tunnels, chugged through high cuttings, and rattled over bridges. Suddenly we’d pass a stretch of Pacific breakers crashing on a lonely beach, and just as suddenly lose it, or meander round one of the sublime low harbours from Waikouaiti to Blueskin Bay. Then back into the hills at Doctor’s Point hauling up to the longest tunnel of all at Purakanui. Eventually the JA’s burst out of the interminable darkness at Deborah Bay and we’d reached Otago Harbour. Hanging high above the steep rickety town of Port Chalmers gazing down on ships at their moorings was the perfect finale to our three thrilling hours in the hills. The flat causeway up the familiar harbour to Dunedin was a satisfying coda. Dunedin Station was cavernous and formal and the cafeteria smelt deliciously welcoming but what I found most intriguing was that, if it was raining, there always seemed to be at least one broken pane in the arching glass roof letting the rain splash down onto the big old platform.

4:30pm and back again to one JA another long tunnel at Caversham took us out of Dunedin onto the Taieri Plains. The journey thereafter had only two meetings to break what, to kids, was becoming a bit humdrum. The first was when relatives turned up to Gore station to pass a shoebox of scones and some amusements through the slit of the carriage window. We could talk but not for long and when we said goodbye our destination was the one last thrill remaining. It was quarter to nine when we pulled into the white wooden Invercargill station, the long Southland evening still shining, despite no daylight saving. There was Uncle George and Peter Keir and sometimes other relations ready to load us into the truck and car and drive us out to Roslyn Bush. Uncle George was Mum’s uncle so our great-uncle, and Peter, one of his sons, a bachelor still at 35, was the be-all and end-all of cousins. That’s why there was always a discreet struggle amongst us to ride home in his truck, any squabbling would disqualify us, so success came quietly to the quickest or luckiest. To awake in the familiar farmhouse with the lino shining, the coal-range warm and the porridge on, rediscovering the tractor sheds, the old red shearing shed, the dogs at their kennels, the yards and the dip under the macrocarpas was a longed-for paradise. We each had space to wander and meditate to our hearts content.

With my brother, Brent the reins man, on a patient farm dobbin

During that first week at the farm the adults made all the prep for our fortnight in Fiordland, although the planning was already pretty much done by our expedition leader, cousin Peter. A competent, generous and funny guy with huge hands and no children Peter was to us the epitome of perfection. His ready laugh ranged from a giggle to a shoulder shaking side splitter, and, impressively, he could remove every skerrick of meat from a chop bone with his pocket knife. He had a truck, money and farms of his own plus he was happy being a kid again. He loved having us around and included us in everything. We simply adored him. Peter’s sister Dorie lived with her family in Invercargill, and they would join us on our tour with their own truck. Sometimes Uncle George’s housekeeper came, at others a farmer from over the back, Mary Murphy, so there’d be six or seven adults and seven or eight kids in the party.

The first exciting morning of our camping odyssey saw us headed to Winton, six in Uncle George’s two-toned Zephyr Zodiac, which was flash but somewhat sedate, and three in Peter’s DeSoto truck which was flash but riotous fun. Others rode in a red Fordson truck which was neither flash nor riotous. At Lumsden we turned left towards Te Anau via Mossburn and Centre Hill. Te Anau was our first camp and the gateway to our favourite lake, Manapouri. The campground was usually empty and we set up our tents wherever Peter thought best. He’d arranged two tents. A ‘women and children’s tent’, classic canvas with a centre pole, green roof, white walls and guy ropes pegging the corner poles straight, then the ‘men’s tent’, a big saggy lean-to affair that Peter had fashioned himself. At its first outing he’d pitched it right beside the square tent, but the men inside were drenched when rain that night slid off the roof of ours into theirs. After that the men’s tent was pitched out on its own, but by the hilarious stories the menfolk told of midnight disruption it was never salubrious digs, or even watertight, they either got used to it or found dryer places in the trucks. In our case there was no disruption. At every stop Uncle George bought a couple of bales of hay from some farmer he knew in the vicinity and when our tent was up we broke open the bales and chaos ensued as we spread the hay throughout. When we’d finished our fun a huge tarpaulin was laid on top and we all slept on that. No sleeping bags, just the piles of eiderdowns, blankets and pillows the adults had included in the packing.

The women and children’s tent with the men’s tent behind. Cousin Peter Keir, left, with our sister Susan, Brent, Mum, youngest brother Kerry, with me and cousin Irene near Peter’s green DeSoto truck.

The high point of our stopover at Te Anau was to take the short drive down the Waiau River and spend the day on a tourist launch cruising Lake Manapouri. Because the huge lake was completely surrounded by bush-clad mountains and the several long arms provided sublime peace, we felt wrapped in the beauty of the mighty beech forest, the sparkling water and the incomparable bird song. Mum, who especially loved this trip, was scandalized one year by an Australian visitor complaining to her friends that ‘there’s too much green’. Georgie was horrified to think that such a philistine was unable to appreciate the matchless beauty surrounding us and she had to work hard to calm her indignation before it spoiled one of her favourite excursions. The smell of tea seems to pervade memories of the 1950s, and I’m sure billy tea and scones were served during a stop on this glittering voyage. Certainly, the hiatus at a precarious jetty gave us plenty of time to take a bush walk in the beech forest to look for black and white robins and emerge awestruck on a pristine beach.

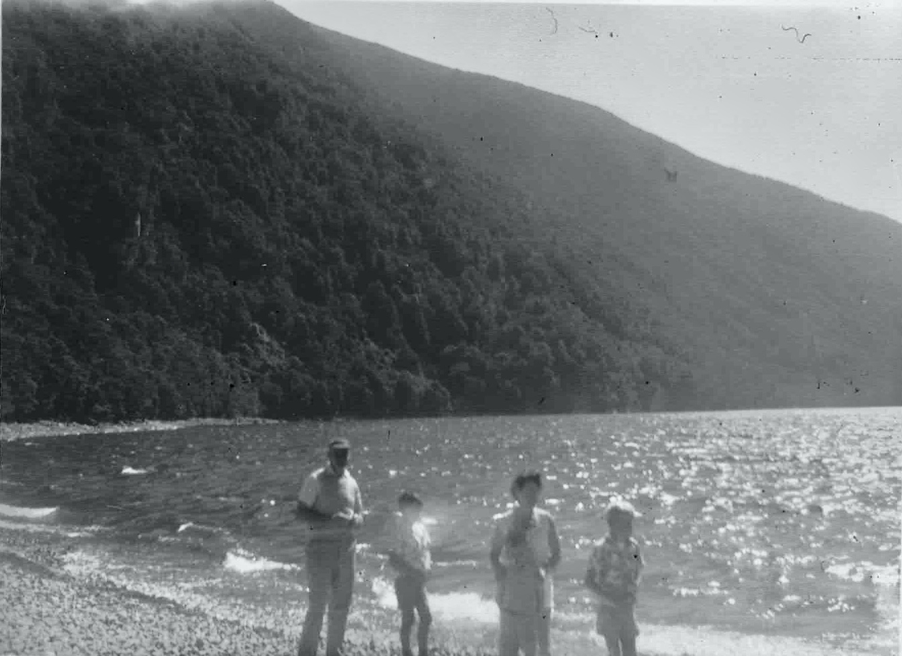

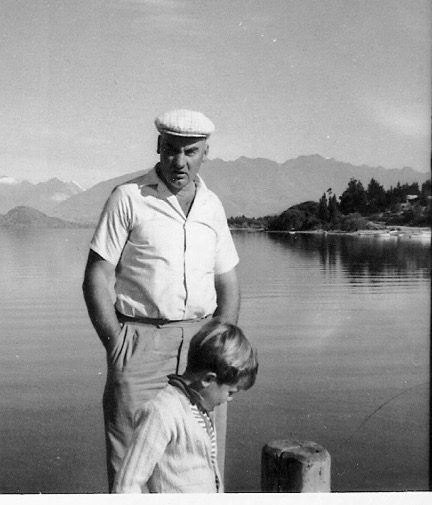

Peter, Mum and we three brothers drinking in Manapouri’s great beauty.

Peter, Mum and we three brothers drinking in Manapouri’s great beauty.

The Manapouri launch tied up to a tiny jetty while tourists wait for the billy to boil.

Although at times we camped at Manapouri, Te Anau was the usual spring board to the heart of our journey, Eglinton Valley. The plan to up sticks and leave for Smithy Creek reawakened a thrilling prospect of mighty glacial valleys, endless beech forest and towering mountains, all to ourselves. Eglinton Valley is wide and flat. The gigantic glacier that carved its walls has long since gone, but its heir, the Eglinton River, has filled the bottom to create endless level sites for a camp like ours. The gigantic landscape dwarfed our dust plumes on the lonely shingle road, yet far from feeling overwhelmed we accepted its familiarity as a giant welcome back to a place we saw as our own. At about the middle of a 75 mile road, base camp at Smithy Creek was conveniently placed to take in all the sights we wanted to visit again in Eglinton. In fact the whole valley was a corridor of attractions.

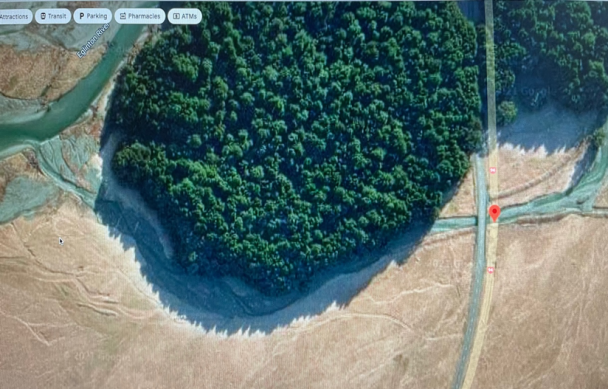

On the way up to Smithys we’d visit Mirror Lakes, two oxbow lakes created when the Eglinton River changed course. The perfect reflection of mountains and surrounding vegetation on the lakes was breathtaking, and it was always good to see a lonely scaup break up the scene as it paddled its way to the other side leaving an expanding wake to gently disturb the picture. Back into the transports we marvelled at an optical illusion: as we drove up a gently sloping road, a mountain straight ahead slowly sank from view and disappeared. We loved to think that on the way back we’d see ‘the vanishing mountain’ appear again. At Knobs Flat, an old work camp where Peter told stories about the road building that had finished only a few years before, there was camping, but he eschewed that ground as well as those at Mackay Creek and Deer Flat for his favourite spot and ours, beloved Smithy Creek. Smithy Creek was a campground of sorts. We sometimes lit the giant concrete fireplace provided, with muscly steel pipes to hold pots, but there were no other facilities. Water came from the rushing rocky steam, and I suppose toileting was a bushy, private, scattered affair. Peter may have arranged a privy, though it’s a detail I find hard to recall. Tents were pitched on the huge sweep of long green grass, a kitchen was established and we settled in for an extended stay in heaven. Not once did we meet another camper there.

Just us as usual. Smithy Creek 1959.

Dinner among the beech trees at Smithy Creek, Peter stands with his sister and her husband.

Some days at Smithy Creek began as a primeval awakening. The drawn tent flap revealed an astonishing scene. Cold heavy dew bent each blade of the long green grass into a perfect curve and the sun lit every silver drop. The shining quivering field looked almost too magical to walk on. The forest produced a rich velvety smell of honeydew, damp leaf litter and moldering logs, the beech canopy so uniform it hid the individuality of each black tree. The air resounded with a colossal chorus of singing birds. Tui and Korimako, Riroriro and Robin, Mohua and Piwakawaka, Kaka and Kea, all strove to top the others to produce a mind-bending symphony. The rushing creek joined in. There was always someone up so human sounds of cracking and chopping mingled with the birds' full on musical recital to enrich the performance. For sheer beauty it was unequalled. Ours was a mountain holiday so days weren’t always astonishing. Rain regularly closed everything in and brought cold - but it made the bush smell good and life never stopped being fascinating. Mornings could be pretty cold for January so the thought of stripping off a jersey and splashing into freezing Smithy Creek entered nobody’s head.

Our campground to the right above the creek.

Cousin Dorrie’s husband Jack and Dad discuss possibilities on a long southern evening.

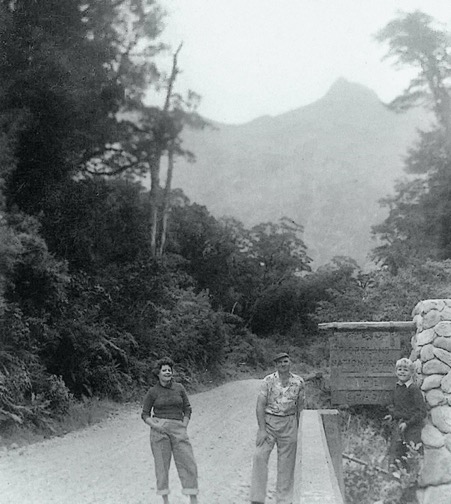

After a few nights beside the creek the time came for us to drive to the zenith of our trip, Milford Sound, much anticipated because of the scary thrill the Homer Tunnel promised. The journey included a few side attractions we liked to take in. Our inexplicable first stop, Cascade Creek, wasn’t one as it was a Lands and Survey camp with huts. We felt it was too tame for our style. Perhaps because it was the only ‘village’ in the Eglinton Valley, we always seemed to pay a visit, luckily a short one.

Bad form at Cascade Creek. Admonished by Uncle George for combing my hair and obscuring my beloved cousin Dorrie, I was still left wondering why we were here.

Lakes Gunn and Fergus, Hollyford Valley and The Chasm were way more exciting. The two lakes were long and on a good day serenely reflective. Nestled within steep-sided bush clad mountains with plenty of peaks and hanging valleys revealing their glacial past the pair succeeded each other. The thin strip of shingle road skirted Lake Gunn on its western shore and Lake Fergus on its eastern. Those travelling in the back of the truck experienced the beauty through a cloud of dust, but we were on our annual trip to Milford, so who cared? If we were too early, or too late for our allotted time to pass through Homer Tunnel we’d meander up magnificent Hollyford Valley. The Hollyford is a real mountain river, and its valley a beautifully sheltered paradise where the vegetation was much more varied than down at Smithys and the sun always seemed to shine. We’d drive not far up Lower Hollyford Road to a swing-bridge over the torrent and while away the time there. Peter eulogizing about the wonders to be seen further up the valley often made me hanker for a camp up there, but it never came to pass.

And so on to the Homer Tunnel. Even with a sojourn at Hollyford we’d always have to wait a while before our turn to drive through. It was half an hour either way. Vehicles traveling from each end had to take their own timing as there was no other system than the instructions on a painted sign. As we waited for our turn we’d marvel at the ruins of a concrete portico that once stood beyond the entrance to stop the tunnel being blocked. Not long after its completion in 1953 it was totally demolished by a giant avalanche and never rebuilt. The shattered concrete and twisted steel reminded us of the daunting power that surrounded us, a power that kept Mum inside the truck. She was not one for over-awesome experiences. As we reveled in the sheer granite faces of the Homer Saddle hanging over us and the un-melted avalanche snow that had dropped in tons from high above she preferred to view everything through the windscreen. One year, when we went with Peter across a humongous avalanche to see a waterfall a rather worrisome rumble above began to grow and we all high-tailed it across the icy snow back to the road. Luckily the small summer avalanche that had been released stopped somewhere higher up and we breathed again. Mum was furious with fear and told us never to ask to go out there again.

Mum’s in her ‘safe place’ as we’re both dumbfounded by the grandeur around us. The others are scattered on fallen avalanches at the roadside trying to make snowballs.

Then the hour struck and the little gathering of cars and trucks started their engines and headed to the portal. The tunnel’s interior was unlined and jagged rock looming out of the darkness seemed to threaten us from every side. Lit only by puny headlights everything seemed eaten up by the blackness. The engines created a muffled ruckus as Peter’s truck packed with spooked and excited campers, closely followed by Uncle George’s Zodiac inched through what we thought of as the most wonderous road in the world. Occasionally waterfalls crashed onto the vehicles, providing a thrilling fright, and at times the road doubled as a stream bed. Even on repeat the experience never became blasé, and the risks of our journey remained a turbulent satisfaction. Having passed through a mountain we’d eventually emerge at the top of the Cleddau Valley to a dramatic scene of countless mountain ridges on either side of the zig-zag descent towards the sea. Waterfalls fell in their hundreds down colossal rock faces into the untouched bush growing on their crumbled flanks, while shining lakes and ponds stood everywhere along the way with their inevitable fringe of harakeke. The breathtaking scale of things seemed to silence everyone.

About halfway down a bush walk took us to a feature we’d all been looking forward to see again. The Chasm. The name itself was exciting enough but the power of water over rock on display always took our breath away. On one side of a footbridge the Cleddau River is squeezed into a headlong dropping torrent and disappears down a hole. A few steps to the other side and it has fallen away hundreds of feet below into a frantic pattern of caverns and white-water bends. The roaring river, vanishing down a perfectly smooth hole, or gushing out from some hidden source to cascade down and disappear again, was endlessly fascinating. The din, spray and wind it created mesmerized us and made it hard to leave although we were inevitably compelled to go by the increasing cold created by crazed white water in a sunless bush setting. No photograph can do The Chasm credit, but there are some videos on You Tube that come close.

At The Chasm.

The heady zig-zag ultimately delivered us to the valley floor where the Cleddau River created a wide sauntering bed for itself to show off its lazy loveliness before it flowed into Milford Sound. One last bend in the road suddenly revealed a busy collection of vehicles in the distance and people outside the Milford Hotel. We’d reached our destination. It seemed a bit strange to be back in society. We felt miffed that these interlopers were sharing the paradise we’d had all to ourselves previously. The THC Hotel, though admirably modern, held no attraction to us, we were in love with canvas and these unexpected ‘others’ seemed to have no idea of the purity of our experience. A tour bus disgorging sand-fly swatting Australians was the ultimate in corny we thought, though the promise of a launch cruise round to the Bowen Falls soon lightened the mood. Forgetting our prejudice we cheerfully joined the rubberneckers already climbing the gangplank.

Milford Sound where the mighty enveloping sea meets the massive glacial-carved rock of terra firma, it’s sheer face disappearing inexorably down into the calm emerald green depths, is miraculous to behold. Milford was the only place we encountered the sea on our expedition through these lands, and the familiar lakes and ponds, rivers and creeks seemed diminished by its vastness. Bobbing around on the glassy surface, breathtaking vistas on every side, with some joker barking platitudes over the launch’s tannoy brought on the kind of reverie never experienced in a classroom. Standing off the Bowen falls, white water roaring and crashing down from above, was predictably awesome. We hoped that there’d been rain to make the falls crazier and louder than normal, but whatever the conditions the Bowen River’s last precipitous gasp was worth a visit. The cruise was not much more than an hour and on our return we straggled around on the foreshore at Milford for a while, enjoyed some kind of picnic then packed up ready for the drive back through Homer Tunnel to Smithy Creek

Dad’s 1957 picture of Mitre Peak on a moody day. Some days were less dramatic but sunny.

Usually the drive back to camp was uninterrupted by side trips, though if we’d bypassed The Chasm on the way in we’d make a visit on the return, just to complete the day. At Smithy’s again we’d be greeted by our untouched camp or, if some adults had stayed behind, dinner on the go. Adults took care of everything. There seems to have been enough of them to handle all the planning and work between them. We did virtually nothing but enjoy ourselves. I remember Mum’s voice ringing round the valley one evening. ‘It’s not a holiday for me!’ she called, stirring the pot over a blazing fire. I don’t know who the remark was intended to notify, and I’m sure it hit the mark, but wrapped in the purposeless wonder of childhood I found it strange that she should think that way. Her cry haunted me until adult necessities replaced purposelessness and I understood, but the wonder remains touchable - as it obviously did with the adults in their better moments.

Susan and the ‘little’ kids.

Riding a mountain beech.

Farewell to Smithy Creek. Time to pack up and get on the road again. Even if we were on the way back to the farm our odyssey was still only half way through. After leaving Eglinton Valley Te Anau then Mossburn passed and we turned left onto a new road which crossed the Oreti and headed towards Five Rivers. We were back in farming country and our beloved mountains no longer closed us in but appeared in their denuded state on the distant sides of wide valleys. Yet excellent thrills awaited as we joined the main Invercargill to Queenstown road bound for Kingston and our first glimpse of Wakatipu. Kingston was a good place to mooch about or have a lunch break. Sometimes we saw the steamship Earnslaw tied up there. But Peter’s mythical stories about the dangers we faced getting to Queenstown from here were both so alarming and so exciting we were itching to get back into it and experience the terror all over again. Kingston to Queenstown was a narrow shingle road that helped accentuate tight corners around lofty bluffs and the dizzying climbs to get there. Built by hand and dynamite in the 1930s our road may have been wider than the original, but not by much. Any meeting with oncoming travelers needed to be negotiated in the tight spots. The Devil’s Staircase was the most famous and scary element of the spectacular ‘highway’. It climbed up by a series of impossible bends to a hairpin right-hander clinging to the vertical face of a towering bluff with a sheer drop to the lake far below. Peter told us that no one had ever found the lake bottom there and advised us not to look over the side. We did of course while our hearts thumped with apprehensive delight. We clung to Peter’s spooky stories so willingly they became part of a ritual, he loved to think he was scaring us, but we all knew he didn’t really want to. Nowadays the highway has been widened and gentrified and the devil and his staircase are barely noticeable, in 1959 the whole road was the epitome of hair-raising.

The final hairpin bend on the Devil’s Staircase seen from the Queenstown side, the road to Kingston in the distance.

We usually reached Queenstown in the late afternoon and hung around for a couple of hours before moving on to our planned camp at Arrowtown. It was a pretty little town of about 1,300 people with the easily discernable Pakeha history common to all inland Otago towns. Progress had not obliterated the built achievements of livelier and more prosperous days and it exuded the sleepy abiding atmosphere of a contented holiday town in an extraordinary setting. Apart from the magnificent lake stretching among the humungous hills ‘sights’ to attract travelers were few. The Bottle House, and a mob of gigantic trout swallowing bread thrown from the wharf basically summed it up. There was of course the graceful Edwardian steamship Earnslaw moored to the wharf with her bell and brasses gleaming, her decks smooth and her white paint immaculate, but we could only look as our appearance never matched her timetable. However, there was a magical alternative, the Meteor. Our over-long hiatus in Queenstown was, in most part, because Uncle George needed to visit a friend he had there. She owned a private hotel somewhere on the hill but that was as much as we ever discovered about her. None were invited to join him in his visit, and there was some curious nudging amongst the adults, but we loved and respected our convivial Great-Uncle far too much to question. To compensate our waiting Uncle George sometimes hired the Meteor on his return to take us on a thrilling speed-boat ride around the inner harbour. We gasped with exhilaration whenever he suggested it and when all the adults agreed he’d summon the captain to come collect us. The cruise was as thrilling as the varnished decks were lustrous and the white captain’s hat added an official importance that made the joy-ride perfect, though it always seemed over too soon. After we disembarked a familiar ritual began, Uncle George and the Captain arguing over the price. One pound for that! was our cue to begin wandering up the wharf to the transports, leaving the two protagonists to a game they seemed to secretly enjoy. Negotiations eventually closed and our jovial patriarch happily guided the Zodiac to Arrowtown, the magical place that we all knew suited us much better than Queenstown.

Peter and Kerry wait for Uncle George on the wharf at Queenstown.

The Meteor, Lake Wakatipu, 1950s.

Arrowtown, that intriguing relic of a town that was, had the vital element Peter prized. Because there were so few other humans around to challenge our claim, it belonged to us. The campground was almost always empty and the one street of gigantic trees sheltering tiny abandoned cottages was a ghost town with a palpable past and almost no present. Wandering in the village in the lingering twilight, peering through the windows of empty shanties, snooping for lost gems in forsaken gardens, imagining dilapidated workshops as they might have been was an absorbing and much beloved pastime. Peter’s history tales and details illuminated the scene. The only tourist attraction was the old jail which you could visit if you knocked at someone’s door and were loaned the key. We seldom did, but that didn’t mean there wasn’t plenty to relish. Days in Otago towns were so much hotter than in our mountains and the Arrow river with its myriad coloured stones and boulders was great for cooling off. The water pipe to Macetown spied from our swimming hole was an enduring enticement. Peter told us the line could be walked for miles up the river to the forgotten old gold town there. We always wanted to try it but long walks didn’t cut it with our ‘50s adults so regrettably it lay undiscovered. Back then there was no sign that Arrowtown might have the glittering future it now enjoys, nevertheless, as others will attest, it was an enormously attractive, inscrutable and much loved treasure just as it was.

The empty campground at Arrowtown, one of our favorites. This photo was probably taken in 1958 as our eldest brother John is with us. Uncle George, who seems ready to drive off, invited his housekeeper Marg. Although the significance escaped us, she loved to say she knitted bed-socks for Winston Churchill!

Goodbyes to favorite places seemed futile when coming back next year was a given so we slipped out of Arrowtown with a sure knowledge that we’d breath its cherished shadowy air again. What’s more we were headed to another famous highway and smelt adventure ahead. It was the track over the Crown Range we focused on now. As we climbed the huge bank that lies behind Arrowtown the countless sharp bends between the steep traverses began almost immediately, as did the clouds of hot Otago dust we had to adapt to on the ‘highest road in New Zealand’. Other clouds accompanied us too, clouds of stories and imaginings of long gone days before the motor. Of drays, and powerful horses who needed to be expert in hauling loads upwards and steadying them coming down. Of wagons, and drivers man-handling the wooden brakes while husbanding their teams over hours of toil. As we climbed and climbed Peter’s folktales carried us back to the ‘olden days’ of goldminers and swaggers, of hardship and luck, of blinding heat and snow, of runaway gigs and cars that crashed off the edge. Sometimes the scratchy little road seemed too tiny for all that history yet each young head was brimming with it. Peter’s lore swelled our pride of place, we felt totally at home, safe in the embrace of our hapu. It all made arriving at the Crown Range summit our own triumph of grit over adversity. The prize? The immense views across the whole wide world.

View over the wide world.

Probably 1960. Mary Murphy is with us.

Nothing could be finer than the long drive down the Crown Range towards Wanaka. Never as precarious as the steep trip up, the descent followed the famous river of gold, the Cardrona. Massive brown hills rolled all around as the heat burned off them and perfumed the breeze. They carried the road past spectacular views of far distant ranges and allowed for wider bends where we could stop and drink the landscape in. The incline was so long we thought the bottom would never arrive, but when it did we pulled up outside the Hotel Cardrona for another gob smacking encounter. The old hotel seemed to be the only building in sight, though there may have been others, yet it was open for business. As our circus provided the only customers we kids were invited into the tiny bar to choose a drink. The publican didn’t seem that friendly, in fact we found him slightly scary, but we got our sarsaparilla, or whatever it was and skedaddled outside to explore the old guy’s otherworldly establishment. Round a courtyard were rooms each opening onto the verandah, more like a shearers quarters than a hotel. Sheds and other amenities all on a lean populated the overgrown garden where we came across a huge cherry tree and helped ourselves. But the stately claw-foot bath took the cake. We’d never seen a tub so tall or so commodious, its gigantic taps served by exposed pipes clamped to unpainted tongue-and-groove The whole bathroom was dusty dry and richly warm from days of hot sun, the only water came from a drip that left a green skid mark above the plug. The picture of an old king stuck on the wall and a dusty soldier’s uniform behind the door completed the décor and made us feel we’d taken a step back in time. From such a wonder we could hardly tear ourselves away.

Peter in the bar doorway. John and Uncle George chew the fat, while the rest of us rush in all directions. Hotel Cardrona 1958.

Back at the bar the others were finishing up their drink. As each empty eight ounce glass hit the minuscule counter the grizzled proprietor snatched it away and swished it through a half barrel of water stationed behind him, gave it a shake then set it upside down on a narrow wooden shelf with all the other glasses. Everyone was wide eyed. We’d never complain about doing the dishes if this style was sanctioned! Although the atmosphere was convivial and, as we later discovered, the old man had been free with his stories, a general feeling developed that we’d had our fun and it was time for us to clear out and leave him in peace. Which we did, but in that short hour his character and circumstances had filled us all with such a unique touch to the past we never forgot him. The Cardrona Hotel wasn’t open when we’d passed by before or since, but our one brush with James Patterson was enough for a lifetime.

Jimmy Patterson behind his bar, the water barrel is just behind him. He bought the Hotel Cardrona in 1926 and died, aged 91, in 1961.

And so on down to Wanaka. From what I remember it was a tiny crib town that we paid little attention to as we were headed for Glendhu Bay campground a bit further round the lake. Glendhu Bay had a splendid beach with a background of massive round rocky topped hills leading to piles of proper mountain peaks towards the west and north. Wanaka was as handsome a lake as all the others we’d enjoyed but had the advantage of being a lot warmer for swimming and Glendhu Bay was the prime spot. This stop was another pivot on our tour. It was our last touch to mountains and lakes, and was the gateway back to familiar civilisation. As a change-up I suppose, Peter one year chose to take the trip in reverse and our stop at Glendhu was the first camp rather than the last. However he can’t have liked it much as we never did it again. Now we were on the edges of Central Otago proper – that warm dry fruit bowl that always confounded us as to how such a desert could bring forth so large a bounty.

What facilities! Uncle George, Mum and Marge Coutts at Glendhu Bay 1958.

Packing up for the last time this year we left Wanaka and headed east aiming for Cromwell and then deeper and deeper into Central Otago proper. During the first phase the huge brown hills and the winsome gold towns we knew and loved made for a satisfying mix of antiquity and juicy summer fruit from one of the countless honesty stalls along the way. Orcharding and its position at the confluence of two great river gorges meant that Cromwell was still a thriving place in the late 50s, unlike Arrowtown and a score of forsaken hamlets clinging to life throughout Central Otago, but it had a very similar look to those charming relics. Classic old pubs, some of stone, a mega corrugated iron garage with doors flung wide where mechanics filled the tank from roadside bowsers, old town hall and library, a greasy spoon restaurant and a couple of tea rooms. Done-up shops mostly had a new façade only, the original building still giving service behind. Driving down the gentle slope of Cromwell’s main street, a bag of nectarines to share and a summer mirage dancing off the schist hillside, the comfort of the old town felt very right. Just past the ubiquitous lone soldier grieving on a plinth a handsome old steel bridge spanned the Clutha River at the Cromwell Gap. The deck high above a swirling cataract was held up by a number of massive stone pillars and the famous bridge boasted a busy main street at one end and a lonely high country run at the other.

Now on the far side of the surging blue Clutha we’d keenly search the opposite bank for dugouts in the high perpendicular cliffs where Peter told us Chinese miners had lived in their search for gold. Marginalized by racism these men had to take what they could where they could, though Peter said admiringly that they had found more gold in the abandoned tailings and the difficult country around the Cromwell Gorge than their Pakeha cohorts ever did. Poetic license perhaps but a dig in the right direction. The smooth sealed road clung to the flanks of steep hills just above the mighty river’s flood level and gave great views of the Clutha’s rocky banks. Before long we’d reached Clyde. Although smaller and less lively than Cromwell Clyde’s main street buildings were surprisingly more substantial. Solid stone buildings like Dunstan House, the Miners General Store, the Court House and elegant Post Office stood amongst some of the tiny wooden premises of the original mining town. To cap off Clyde’s superior architectural collection the white Masonic Lodge of 1869 was a perfect, if somewhat battered, Grecian temple in miniature complete with Doric columns supporting the tympanum. The street was impressive even if the town baking in the heat was virtually dead.

The difference between Clyde and its twin Alexandra was marked. Alexandra began as an outlier of Clyde, in fact Clyde was Upper Dustan and Alexandra Lower Dunstan. Only a few miles apart they diverged dramatically though the years as Alexandra found new sources of income once the gold had gone and Clyde didn’t. The seat of the district’s local government Alexander grew to become the main town of Central Otago and its historic charm diminished as its importance grew. Still, planted in the glorious heat of Central Otago, Alexandra was well made and cared for and had the distinction of being the first ‘living’ town we’d come across on our trip. It had little interest for Peter however and we let it pass, it’s only significance was that we re-crossed the superb Clutha River here, through the stone arches of the old bridge until 1958 and then the excitement of the new steel bridge after that. Once we’d left the town we’d find a favourite orchard stall to stop for a summer feast. Hanging out together around a homemade market stand displaying its bounty in wooden trays slurping on a delicious peach with the smell of summer fruit filling our nostrils was heaven itself and instilled in us the certain belief that Central Otago stone fruit was the best tasting in all the world.

We carried that sublime smell into the car and trucks in the cases of fruit the adults bought and set off for the farm. Just one more exciting prospect lay ahead, a visit to Roxburgh Dam. The first dam on the Clutha it had opened in 1957 and was to us the epitome of must-see modern no matter how many times we returned. Gasping above tons of Clutha water rocketing down the spillways we watched in awe as it crashed in a gigantic fan of spray when it hit the rise at the end. There it joined the powerful turbulence of that part of the river exiting the penstocks. Together they formed a picture of incurable disruption and chaos, yet in the distance we could see the beautiful river reformed and flowing on its blue sinuous way as if nothing had happened. Even on those rare years when we didn’t make our grand camping passage, Uncle George and Peter would take us up to Roxburgh to see the dam and feast on the strawberries that grew so well in that district. Pick-your-own was the order of the day and we’d lay among the rows to gorge on huge warm strawberries, sometimes dipped into the Agee jar of thick cream the house cow had given Uncle George that morning.

Atop Roxburgh Dam c1960.

First Alexandra and then Roxburgh began slowly to awaken us from the reverie our beloved family journey had taken us on. The feeling was melancholy but bearable considering we were full from the new wonders we’d seen and those we’d experienced again. At Raes Junction we turned our back on the Clutha and all that had come before and joined the road to Tapanui and Gore. Occasionally we stopped over in Gore to visit those surviving members of our family retired into town from our Great-Grandparent’s farms at Charlton. Their houses, hushed but for a ticking clock, seemed dim, with holland blinds drawn down almost to the sill, yet all that could be polished glowed. Their welcome was always warm and quaintly old-fashioned, their recognition of us kindly and reassuring. In their presence we were happy to be still, to watch and admire their novelty. We always seemed to drive away with a bag of homegrown red king potatoes.

As we pulled up outside the Roslyn Bush farmhouse, another satisfying circumnavigation completed, we knew that in a few days we’d be back at the Invercargill railway station to catch the northbound limited home. The long day’s journey was enjoyable but the feeling utterly different. The thrilling anticipation was gone replaced by a dreamy quietude that comes with total fulfillment and a return to our own tight family group bound for another year of doings and tellings, obligation and discovery. Tired and replete, relaxation overcame us.

Arriving at home it was fascinating to see how different our usual haunt was. The sturdy state house looked lost and drab, the lawn shaggy, and there was dust in uncommon parts. While our quiet, adventurous and beloved Dad paid six and six to the Blue Star taxi man and brought the luggage in, the gates of heaven were imperceptibly squeaking shut.